4 October 2018 sees the 60th anniversary of the first commercial jet airliner flights across the Atlantic. Our Comet G-APDB, here at Duxford, was one of two aircraft that took part in that historic crossing.

It all began when two push-bike mechanics, Orville and Wilbur Wright, flew the first, powered, heavier-than-air machine at Kill Devil Hills near Kittyhawk Beach North Carolina in 1903. Man had conquered the air. Dreams of flying as a means of transport began to form. Despite huge advances in aviation brought on by developments during the first World War, flying was only for the super rich and over short distances. This was soon to change. In June 1919 two Englishmen, Alcock and Brown, flew their bomber-derived Vickers Vimy biplane non-stop across the Atlantic from St Johns, Newfoundland, Canada to an ignominious landing in a Irish peat bog. Trans-Atlantic flights had begun.

The Germans however continued with airship development and built the Graf Zeppelin and later the Hindenburg. These giants of the sky flew non-stop many times over both the north and south Atlantic between Europe and north and south America, with the Graf Zeppelin making the first crossing to New York from Germany in 1928.

The airline that originally operated the early Zeppelins was the German airline DLAG, which having started operations in1909 was the world’s first commercial airline. The company disappeared in 1935 following a merger with another airship company that continued to operate the Zeppelins across the Atlantic until the Hindenburg disaster forced airship operations to cease. Both the UK and the US concentrated their efforts on building seaplanes to complete the crossing.

In the early 1930s Imperial Airways were using Short Empire flying boats on the route. These however did not have the range to cover the route non-stop with a full load of passengers so another solution was needed. A radical idea was hatched. A Short Empire flying boat would have a smaller aircraft attached to its back, carry it to height and then release it to complete the journey.

This was the Short Mayo Composite. The two aircraft were named Maia and Mercury, with Empire flying boat Maia carrying Mercury on her back. After test flights in 1937, July the following year saw the service launched. A flight from Foynes flying boat base in Ireland, piloted by Captain Don Bennett, touched down in Canada close to Montreal completing the first non-stop East to West crossing by an aeroplane.

The following year this success was overshadowed by the mighty German Focke-Wulf Fw200 Condor aircraft of Lufthansa. This land based four-engine long-range airliner flew from Berlin non- stop to Floyd Bennett Field in New York with a flight time of 25 hours. This was the beginning of the end for the flying boats. With the onset of the Second World War, German airline operations were suspended and the Condors were used by the Luftwaffe as long-range bombers over the Atlantic looking for Allied convoys.

Boeing, meanwhile, had introduced the Boeing Clipper flying boat in 1939 and three had been bought by BOAC. These luxury ships of the sky had the range to carry 74 passengers across the Atlantic, a distance of over 3500 miles. Between Pan Am and BOAC over 84,000 passengers, mainly military personnel for the war effort, were carried across the pond. These Boeing Clippers were considered to be the epitome of luxury travel by flying boat. BOAC operated them from 1941-1948 before, like all the other airlines, concentrating on land-based planes as many more runways became available. The age of the flying boat was over.

As a brief aside, although flying boats very quickly became obsolete on the transatlantic run, the very last crossing by a genuine large flying boat was in 1993. A Sunderland was restored to flying condition over several years by Edward Hulton in the UK. Sadly all plans to make its operation a financial success failed and the aircraft was sold to Kermit Weeks for his museum in Florida. After the transatlantic crossing Kermit displayed it at a number of airshows in the US before grounding it for good at his Fantasy of Flight museum in Kissimmee. This museum has now closed so the fate of the Sunderland is unknown.

1946 saw the start of a new era with Pan Am introducing Douglas DC-4s on the Atlantic route with a New York to London flight time of 17 hours 40 minutes. Later that year, early model Lockheed Constellations joined the route and cut the time down to 15 hours 30 minutes. To compete on the Atlantic route, BOAC were given permission by the British Government to buy six Constellations as no suitable British airliner was available.

Boeing were not going to be left behind in this new long-range aircraft market and had been working on a passenger version of its C97 freighter, which itself was derived from the B29 Superfortress bomber. In 1949 Pan Am became the launch customer for the Boeing Stratocruiser or ‘strat’ as it was lovingly known by its crews.

The following year saw BOAC take delivery of their own examples and these became the Queen of the Skies across the Atlantic. BOAC continued to operate the Strats until 1959, however they were very costly to run and fares were particularly high to cover costs. But when short of aeroplanes following the grounding of its Comet fleet, BOAC was happy to buy five ex-United examples despite the high running costs.

In 1952 BOAC became the first airline in the world to introduce a jet-powered airliner when it took delivery of the revolutionary De Havilland Comet 1. This aeroplane was unable to challenge the dominance of the American piston engine fleet that plied the Atlantic crossing as with the early Ghost engines and relatively small fuselage it just could not carry enough fuel and was used instead on BOAC’s ‘Empire’ routes down to Africa, India and onwards to Australia making several stops along the way.

Following the grounding of all Comets after the unexplained crashes, the Atlantic continued to be crossed by big piston powered airliners mainly of American design.

For a more luxurious but longer crossing, the liners such as the Queen Mary were carrying passengers with more modest wallets as well as the uber-rich. The Queen Mary was one of several famous liners that competed for passengers with the planes flying above, but this was not to last long into the jet age.

With the Comets’ grounding, de Havilland took the opportunity to carry out a major redesign not only to address the structural failing of the early examples but also the size, thirsty engines and short range. The new bigger, more powerful and longer-legged Comet was named the Comet 4. Whilst all this work had been going on at Hatfield, over in Seattle the Boeing company had also been building a Jet airliner the Dash 80 which the world would soon know as the Boeing 707. It incorporated all the lessons so painfully learned from the Comet programme.

Meanwhile the new Comet 4 made its first flight in April 1958 and the first examples were delivered to BOAC in late September the same year. A few days later BOAC positioned Comet 4 G-APDB to Idlewild airport New York (now JFK) whilst its sister ship G-APDC was readied at London Airport (now Heathrow). On 4 October 1958, these two aircraft took off simultaneously to cross the Atlantic carrying forty-eight passengers and VIPs.

G-APDB, flying east to west, had on board Basil Smallpiece and Aubrey Burke, Managing Directors of BOAC and De Havilland respectively. The flight in this direction was made non-stop in six hours eleven minutes, but PDC coming from London had to make a fuel stop in Gander Canada. Thus began regular jet powered scheduled passenger flights across the Atlantic.

These BOAC flights beat the planned operations by Pan Am using Boeing 707s by just over three weeks. The two historic Comets had two different fates with PDC eventually being scrapped whilst PDB the first commercial jet airliner to cross the Atlantic west to east, was retired in 1974 to the British Airliner Collection at Duxford. Having left BOAC for Malaysian and Singapore airlines, PDB finished its flying career with Dan-Air. Today she is painted in the 1950s BOAC colours of that momentous day sixty years ago.

Just two years after this major PR coup, BOAC introduced Boeing 707s on the Atlantic route. As a small nod to the Buy British strap line of the day they ordered their 707s with Rolls Royce Conway engines. BOAC had also planned to introduce the new turbo- prop Britannia on the Atlantic run but due to long delays in its introduction they again obtained Government approval to spend US Dollars and purchased a number of Douglas DC-7Cs to support the Comets. These with the Lockheed Super Constellations and Starliners were the last of the great piston engine fleet to be used by various airlines on the crossing.

The jets began to arrive thick and fast. Once again it was the American manufactures that reaped the benefit of the development of the Comet, with the Boeing 707 and Douglas with its DC-8 filling most of the airlines’ orders for transatlantic aeroplanes. BOAC at the time wanted to buy more Boeings but was forced by the government (BOAC was state owned at the time) to order Vickers VC10s the first of which entered service in 1964. Although not as cost-effective as the Boeings the VC10s were adored by their crews and passengers alike and the airline kept them in service until 1981, long after their last Boeing 707 had departed for pastures new, flying holidaymakers to the Costas with British Airways Airtours.

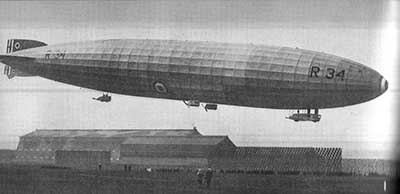

Despite the lack of success with sales, the British aircraft industry was always in the lead on this iconic route. First non-stop crossing with Alcock and Brown, first commercial round trip with the R34, first non- stop passenger aeroplane crossing with the Shorts Mayo, first jet airliner crossing with Comet 4 and there was more to come.

In March 1969 the Anglo-French Concorde first took to the skies. This airliner was to be the only supersonic type to successfully operate across the Atlantic when it entered service with BOAC and Air France in 1976. The Russian TU144 was seriously flawed and only had a short service life within the USSR and the American Boeing SST programme was cancelled. Once again the British aircraft manufacturers had achieved a first across the Atlantic, but this was to be the end of their dominance as the industry gradually collapsed into the shadow of its former self it is today.

Flying until 2003, the British Airways and Air France Concorde fleets crossed the Atlantic thousands of times making the trip from London to New York in just over three hours. Politics and world events eventually combined to force the airlines to retire their fleets and all but two Air France examples ( one destroyed at Paris another scrapped at Dakar) have been preserved at airports and in museums around the world. It was thought at the time supersonic travel would never return to the Atlantic but at the time of writing there are a number of companies actively building smaller airliners which may see the return of breakfast in London, lunch in New York and a late dinner back in London.

Boeing meanwhile had another string to its bow. Having lost the contract to build an outsize freighter for the USAF to Lockheed and their Galaxy, it revamped the design to meet a request from Pan Am for a very large passenger aircraft capable of carrying over four hundred people. They called it the Boeing 747 Jumbo jet. The airlines flocked to order this new kid on the block for which Boeing had needed to build a new factory just north of Seattle in Everett. This factory was the largest building by area in the world.

The introduction of this giant was not without problems as the massive Pratt and Witney engines used were a completely new design from the old well-developed ones used on the smaller jets. Many a 747 was parked up around the world with blocks of concrete hanging from the pylons awaiting new engines. When the first 747s were delivered to BOAC their pilots went on strike for ‘wide bodied’ payment and refused to fly the new plane.

To make the best of the situation BOAC removed all the Jumbo’s engines and leased them out to other airlines such was the demand for spares. Boeing were understandably concerned, but this was nothing like as bad as the problems to come when they introduced the B787 Dreamliner in a few decades time. Up until the B747’s entry into service with Pan Am and TWA in early 1970, flying had been for the rich few who could afford the tickets. Airlines formed cartels to keep the prices high and exclude low-cost competitors off their routes. This changed with the introduction of the Jumbo jet and the economy of scale it provided allowing fares from London to New York to be set at £103 return.

In 1977 Laker Airlines was finally allowed to offer its low-cost Skytrain service from Gatwick to New York. Their prices were around a third of the cost of a major airline ticket. This, along deregulation, caused prices to tumble and flying for the masses had arrived. Some of the major airlines found they could not compete in the new lower-cost travel market and household names Pan Am, TWA, Swissair, Sabena, and many more found themselves going broke and ceasing operations or being merged into other airlines. It’s a fact that in 2018 there are only three major airlines left in the USA : Delta, American and United. Here in the UK the only airlines competing on the North Atlantic route are British Airways and Virgin.

Wide-bodied jets became the norm on the Atlantic run with the Boeing 747 being joined by the Douglas DC10, Lockheed Tristar and late comer Airbus with the A300. The Airbus A300 was the world’s first twin engine, twin aisle aircraft but with only the two engines it was forced by ETOPS (Extended Twin Operating Procedures) rules to adopt a flight path that kept it within a certain flying time of an airfield. It was only with the advent of the four engine A340 that Airbus could compete on equal terms with the other manufacturers.

It was, however, the 747 that gained the lion’s share of the orders and for nearly fifty years has reigned supreme on the blue ribbon transatlantic route. But everything has to come to end and as of 2018 Boeing are building only freighter versions of the Jumbo. Modern twin-engine aircraft like Boeing’s own 777-300 and the Airbus A350-1000 are able to carry almost as many passengers, typically 366 for the Airbus.

With this being achieved with just two engines, the economics have swung against the four engine machine. Only Airbus with its much newer four engine A380 still competes in numbers with the twin engine aircraft. Most of the world’s major airlines have either retired or drastically cut back their fleets of 747s None operated by any of the major US airlines. The future would seem to be that after fifty years at the top, modern twin-engine aeroplanes will take over the mantle of Queen of the Atlantic. With Boeing’s composite 787 Dreamliner offering huge cost savings over the older generation jets, the low cost airlines are now dipping their toes in the transatlantic waters, will this mean even lower prices?

On that eventful day in 1958 when BOAC flew two of its Comets across the pond, they were the only jet airliners in the sky over the Atlantic Ocean. In summer last year there were on average 431 non- stop jet passenger flights a day just between Europe and the USA. Remember that Lufthansa Fw200 Condor flight from Berlin to New York in 1938? It took twenty hours to make the crossing. Today you can be whisked from Berlin to JFK in just under nine. With the seemingly continual increase in passenger numbers year after year just how popular can pond hopping become? The aeroplane and especially the Boeing 747 have brought worldwide travel to the masses, no more so than on that special route The North Atlantic. It’s hard to believe the first time it was crossed by jet was only sixty years ago!

Registered Charity No. 285809