Clear?…Contact !

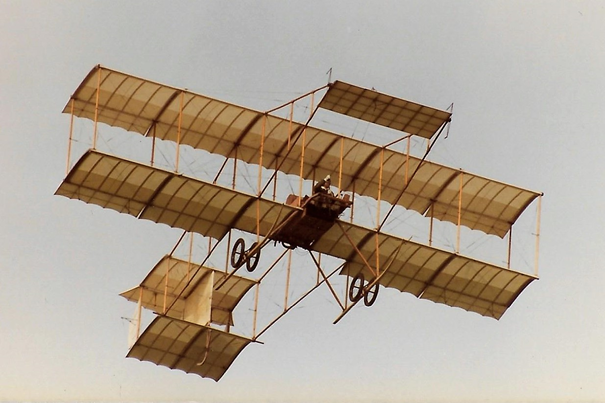

These very words were most likely heard on the beach at Kill Devil Hills near Kitty Hawk, North Carolina on 17 December 1903, when Wilbur started the engine for his brother Orville piloting their Wright Flyer prior to making man’s first powered flight in an aeroplane. Starting an aero engine has come on a bit since then but the principle remains the same. You still need fuel, ignition and rotation to start any engine whether piston or jet. How many times have you been sitting in an aeroplane and not given it a second thought as the engine bursts into life. The fuel is supplied via a carburettor or fuel injection system. The means of ignition comes from a spark plug (like your car) for a piston engine or a high energy ignitor (like your gas oven) for a jet. This article gives an insight into the different means used over the years for achieving the final part of the starting trio, that essential initial rotation.

The first means of turning over an aero engine was the simplest: by hand. At that time cars were also started by hand using a crank handle. On an aeroplane the prop was rotated by hand swinging. Electric starters and batteries of that era were too heavy for these very light and underpowered aircraft so pulling the propeller round by hand was the only solution available. Many old or small aircraft are still started this way today. If all is well with the engine and it’s having a good day the motor may start up on the first swing but often the poor prop swinger has to try several times before the engine coughs into life and this can be exhausting. As aero engines became bigger it was not unusual to see two guys linking hands and pulling together in an attempt to turn the engine over

Engine development began to gather pace during the First World War when aircraft were used as fighting machines for the first time. Even with large rotary engines such as the Clerget and Bentley, hand starting was still the order of the day. Rotary engines came to an end after the Sopwith Snipe and its Bentley BR2 motor. Despite the advent of the in-line engine nothing changed on the starting front. It just got harder to swing the prop as the flywheel effect of the rotary engine was lost.

Between the wars the RAF re-equipped with a large number of aircraft from the Hawker stable: Hart, Demon, Hind and Fury. These were all built along similar lines and featured a large engine such as the Kestrel and a big prop which was rather high off the ground making it very difficult to hand start. To overcome this problem there had at long last been progress in the starting procedure in the shape of the Huck’s Starter. This was based on a car, usually a Ford Model T which was fitted with a long shaft, mounted above the windscreen, poking out in front of the car. This shaft could be clutched to the car’s engine allowing it to be rotated. On its end was fitted a coupling which would mate to another on the propeller hub of the aircraft to be started. The Huck’s starter would drive up to the front of the Hart, Hind etc, engage the starter shaft with the propeller hub, the driver would let in a clutch and rev the car’s engine to rotate the shaft and the aeroplane’s engine to enable it to be started. Sounds very Heath Robinson but this set-up is still in use today with the Shuttleworth Collection at Old Warden when starting their vintage aeroplanes.

By the 1930s aircraft began to be fitted with electrical systems and when engine-driven generators became available to recharge the batteries, electric starting became possible. This was of great importance as at that time flying boats were becoming increasingly popular. This ruled out any means of hand starting as operating from water made hand prop swinging impossible. Smaller land- based aircraft also began to be fitted with batteries and electric starters. These were often helped during the start by a ‘Trolley-Acc’. Accumulator was an old word for a battery and a Trolley-Acc was just what it says. A trolley full of accumulators to give the aircraft batteries a boost, like a jump start on a car. These can still be seen in use today.

The German built Junkers Jumo engine used during the Second World War used a Coffman starter. This was basically a big shotgun cartridge without the shot! The exploding gases would be vented from the starter straight into either the cylinders of the engine or a geared drive to turn the motor over. Due to the cost of the cartridges this was an expensive way of starting engines and subsequently was not taken up by the civilian market. Another popular way of starting piston engines was by use of an inertia starter. This relied on a large flywheel being spun up and then clutched to the engine thus rotating it using the inertia of the flywheel. The flywheel was normally spun up by an electric motor and found much favour in the big American-built radial piston engines used in the Second World War and also on US- built airliners of the 1950s. To start the engines on these airliners the flight engineer would have to do the ‘three finger dance’ on the overhead panel switches. Powering up the starter, engaging it to the engine and priming the engine all at the same time.

With a radial engine that has not been started for a while it’s essential to turn the engine over slowly a couple of times to gently pump out any oil that has drained down into the lower cylinders. If this is not done and the engine is started then internal damage can occur as the piston attempts to compress the oil. Sometimes it’s possible for the ground crew to ‘pull through’ the props before starting, if not the engine can be turned over slowly on the inertia starter with the engine ignition switches at off. A much easier way to get rid of any oil in the cylinders. A typically British take on the inertia starter was fitted to the Fairey Swordfish naval torpedo bomber. Instead of an electric motor to spin up the flywheel, two Naval Ratings would fit a crank handle in the side of the cowling just behind the engine and jointly hand crank like mad to spin the flywheel.

When jets first arrived on the scene the early aeroplanes had very low power engines, so again all effort was made to cut down on weight. A popular method of starting was to revert to the system used on the Junkers Jumo piston engine: the cartridge or Coffman starter. As all these early jet aeroplanes were for the military the cost of the starter cartridges was not a problem. A cartridge start is always an impressive sight with a big black plume of exhaust shooting out of the side of the engine. One can just imagine the sight of a mass start by a squadron of Venoms. The gases from the exploding cartridge would be channelled directly over the engine’s turbine or through a small turbine starter, like water over the wheel of a waterwheel, this starter turbine would spin up and being geared to the main engine compressor shaft would thus turn the engine over.

The Rolls Royce Avon engine was fitted to many of the RAF jets of the time: Hunter, Swift, Canberra Lightning, Valiant and the Navy’s Sea Vixen and Scimitar. Some aircraft used the cartridge start others an electric starter motor. The Lightning, however, used an unusual means of starting with a chemical start system using an Isopropyl Nitrate called Avpin. This was a liquid stored in an onboard tank which would be mixed with fuel then ignited electrically and the resulting exploding gases used to spin the engine in a similar way to a cartridge start.

As can be imagined cartridges and barrels of Avpin are not cheap and are also a major inconvenience if the plane lands away from base or one that does not have the necessary equipment in stock to re- start the engine. This would not do for civilian operations. When de Havilland designed the first jet commercial airliner, the Comet, its de Havilland Ghost and later Rolls Royce Avon engines were built for electric start with conventional starter motors and could use the aeroplane’s internal batteries for starting. This trend continued with the early jets and turboprops, both the Viscount (Rolls Royce Darts) and the Vanguard (Rolls Royce Tynes) had an electric start system running off, in the Viscount’s case, four batteries and for the Vanguard, six. Many small business jets today still use electric start systems either with a conventional starter motor or a starter-generator unit which once it has spun the engine up for starting becomes the engine electrical generator. Such a system was fitted to the Viper engines on the HS125. Today, Auxilliary Power Units (APU) are electrically started as they are based on very small jet engines.

To spin up even a medium size jet engine fast enough for it to start requires quite a big powerful and heavy electric starter, so as engines became bigger a different system was required once again to save weight. What we have today and have had for many years are air starters. These small turbine units are fed with compressed air either from the on board APU or from a ground cart and are normally fitted to the engine gearbox, driving it to spin the compressor shaft, exhaust air being ducted overboard. The compressed air is controlled into the starter by a start valve which will close once the engine reaches a certain rpm. If this fails to happen the first thing the ground crew will notice are sparks and pieces of metal flying out of the starter exhaust vent as the starter motor self- destructs due to over-speeding.

The procedure to start a modern Jet engine is very straight forward as all the monitoring and control is taken care of by the engine FADEC (Full Authority Digital Engine Control) system. Gone are the days of prop pulling through, priming, running up inertia starters and carrying out the three- finger dance to start a big radial engine. No more need for explosive cartridges or corrosive chemicals and big heavy starter motors with banks of batteries. As an example, today’s Airbus A320 has just two batteries only slightly larger than those used in a large car. These are used to start the APU or for emergency power. Also fitted is an APU for engine starting anytime anywhere with a fully automated start system. All the pilot has to do is start the APU, switch on its bleed air, place the engine master switch to on and select start. He can then sit back and watch the magic begin. The engine control system will open the start valve and air from the APU will spin up the starter motor and the engine will start to rotate. At a certain rpm the fuel will come on followed by the ignitors. The control system will then monitor the temperature of the engine as it winds up, how fast it is accelerating up to idle speed at which point it will have switched off the ignitors and closed the start valve. If anything is outside the normal parameters the system will automatically shut down the engine and bring up a message on a display screen telling the pilot what has gone wrong.

Hope you enjoyed this technical tale of the history on how to start an aero engine. Next time you are sitting on a plane and the Captain says we will be starting engines in a moment, you will now know what’s going to happen!

‘till the next time Keith

Registered Charity No. 285809